Slicing Fractions

Illustration by Ayo Arogunmati

At the point when you need more money to grow your idea, artistry or business, there are two methods to finance the growth of the venture. Equity is the first option and is more expensive but provides more flexibility to build the venture while debt, the second option, is cheaper, except it requires regular payments to the lender. For those early in their venture, equity is the best option and beyond the family and friends stage of the business, it will come from external money men or women. The amount of money provided by these financiers differ s based on what you plan to do, and how much they will get back for taking this risk. In the startup world, funding comes from angel investors or venture capital firms. For an artist, emphasis on recording artists, the record labels are the venture firms while the angel investor might be a wise guy. The decision to give up some control of the venture is not easy, but using simple methods to evaluate the opportunities can eliminate future problems.

Books, magazines, conferences and free public resources are available to startups to read and to learn the why, when, and how to take on external financing, but recording artists have to dig this information out of the brains of executives in the industry. If an artist is asked to describe how their valuation is determined, it would not be a surprise to get many variations from the exercise. Some artists will base it on their record sales, both physical and digital, tour revenue, merchandise sales and endorsements. All are valid ways for an artist to determine their valuation, and each of these methods takes into consideration most of the required variables to calculate a valuation, however, the focus of these methods is on revenue generated, thus missing components that provide a better estimate of the value of an artist’s enterprise.

Valuation is a function of cash flow, growth, time and the discount rate and there are tradeoffs between these properties that artists must think about when calculating the valuation of their venture. Without a doubt, the assumptions can lead to subjective valuations that give an inaccurate picture on how to sell fractions of the venture. Artists, while focused on the creative part of their enterprise, should be aware of these properties to decide when it makes sense to sell off part of their ownership to record labels.

Tory Lanez had a recent public condemnation, expressing his dissatisfaction with his record label Interscope. It is not uncommon for artists to publicly criticize their labels for a variety of issues including budgeting, advertising, marketing, and touring. In any business relationship, it is inevitable that the two parties will experience speed bumps, but Tory’s situation prompted the thought on how to reduce the likelihood of speedbumps between artists and their labels. There are no details on Tory’s displeasure with Interscope, but given that it appears to be a one-sided beef, the logical conclusion is that the artist, in this scenario Tory is on the short end of the dispute.

The relationship between artists and record labels is similar to the relationship between startups and venture capitalists, so a similar process to explain selling slices of ownership in a startup can be replicated.

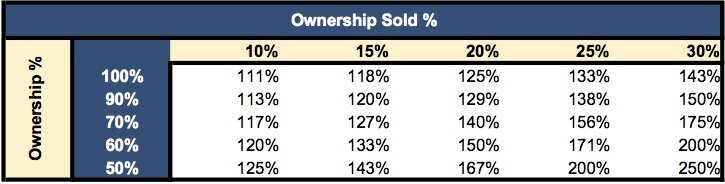

The way to assess what slice of your ownership to give up is to consider the equation [1/(1-n)], where n is the percentage of ownership requested by a label from the artist.

For example, if Atlantic Records is seeking a 10% interest in your creative work. Based on the equation, the breakeven value, which is what you require to get you back your full ownership is 1/(1-0.10) is 1.11 or 111.1%. The deal should only be done if you believe that Atlantic Records can help you generate value greater than 11% for the work you do. Any increase above the 11% means that there will be more value-added by giving up the slice of creativity.

Despite the narrative that record labels do not add value, what is certain is that the good ones do add value to their top artists so the labels do ask for more stake in an artist’s venture. If a top tier label requests for an ownership percentage of 30% from an artist, using the same equation, the breakeven point is at 1.43 or 43%, therefore the label would have to deliver a very high return for the artist to take such a deal.

Breakeven points for different ownership percentages that any artist can use to assess whether more value can be generated using a record label’s advance.

Artists talk about having the right team around to build an infrastructure that is sustainable in the long term. There was an interview by Young Ma in 2019 in which she discusses how she is without a label and manages the most of her career independently. She gave an example on one member of her team who she is grooming to become a key member of her team. She did not elaborate on the terms of the compensation for this friend, but it is important to know how to think about compensation for this member of the team.

What we know is that salary is the primary tool for compensating employees in any venture. However, an equity perspective can also be used to determine exactly how the artist should compensate their employees.

Using a hypothetical example in which Tory’s hires a new photographer to be part of his team, how should he compensate the photographer. The equation to use is an inverse of the equity equation stated above - [(i-1)/i], where “i" is the sum of the current value generated by the artist plus the incremental contribution of the new employee to entity. So, if we assume that 10% will be added to the business with the addition of the photographer the result is that the employee’s equity should be 9% [(1.1 -1)/1.1] of the entire company. But because employees tend to take their compensation in salaries, the artist has to take this into consideration and reduce the equity ownership accordingly.

If we continue with this scenario and imagine that Tory wants to make a 15% profit from the work that the photographer does for his business then Tory needs to adjust the equity of 9% downwards to recognize the photographer’s salary and profit that he wants to make off the increase in revenue. The additional 15% will represent a 13% decrease to the original equity of the photographer, which will now be 7.83% (9%-1.17%).

Finally, the artist has to consider the value of the overall business and the amount being paid to the employee. If Tory values his entity at $5 million after five years and the photographer is getting paid $100,000, then this percentage has to be removed because he or she is already taking part of their ownership as salary. This means that the photographer is taking another 2% from the initial 9% equity, so the final equity that should be offered this photographer should be no more than 5.8% of the entire company.

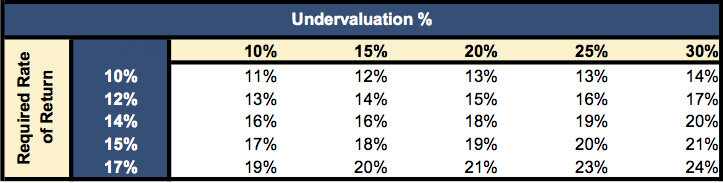

Another problem artists have is how to determine when to buy back their ownership from record companies. The record business is a web of components that are complicated to navigate and the thought of working through the complications can deter an artist from attempting to repurchase their ownership. An artist should keep a close watch on the perception of their value especially when faced with a large undervaluation by the record label.

From the public comments by Tory Lanez, he feels undervalued given his output with respect to his latest Chinx Tape. The album features remixes top RnB tracks from the 2000s with solid production. If Tory is undervalued, then then the record label is yielding way more than their required return for investing in Tory.

There’s an equation that can be used to determine the rate of return an artist can recapture if they are able to repurchase their ownership from the record label. The equation is [record label required return/(1-% undervaluation)], which is equal to the rate of return on acquired ownership. The equation may seem intimidating but all it says is that if the record label invests in an artist and wants a 10% return but is undervaluing the artist by 10%, then instead of a 10% return they are getting 11.1% return. If an artist feels that they can get this 11.1% on their own, then it makes sense to get that ownership back from the company.

Rates of return for different levels of undervaluation of an artist.

There are some drawbacks to the proposed methods to given the complication of the music business with its component parts such as the record labels, publishers, mechanical royalties, song recording royalties, marketing, distribution, and streaming. There are hidden costs that may not be measurable using these simple methods. The point though still remains that assessing when to give up ownership still matters.

Notes

[1] Creating Shareholder Value by Albert Rappaport

[3] Simple scenarios have been used to communicate the ideas of these equations. There are more factors that should be considered by the artists beyond just plugging in random numbers that don’t provide any great feedback on when or how much ownership to give up

[4] There is at least one artist that complains about their record labels each year. Sometimes skeptical of the point of it all as many of these problems are likely better not being discussed in the public domain. Record labels are not inanimate objects, but consist of individuals with a job to do. It is better to find a new way to do record label speak or find people to do it on an artist behalf

[5] Recognizing the oversimplification and criticism of the post is already captured because again these are just simple rules for a simplified assuming non-complex scenario

[6] Southern artists have been the best trained at understanding these concepts given their independent streak before Hip Hop relocated to the south. The deals that many of these southern artists and record labels, for example, No Limit Records, were able to obtain will be the deals of the future as the leverage moves to the artist and distribution gets cheaper.

[7] Of course, if there is a smaller ownership percentage requested by Universal for the same amount of money, then you should take that deal.

[8] Evaluating employee compensation beyond salary involves more math than warranted for this post. The big takeaway is that employees in a new venture are better off taking the equity and capturing the upside. Salary protects the downside but will lead to a lower future payoff.

[9] An angel investor can be a pool of individuals and not just one person. Angels are more sophisticated in the startup space leveraging their money, expertise, and relationships. Artists get the money but are usually missing the expertise and relationships.